On the Omnipresence of Conspiracy Theory

Brief remarks on a now meaningless term

The average American citizen once rested easily knowing two things: conspiracy theories are not true, and that he himself is not a conspiracy theorist. No matter how poorly informed this average man is, he takes solace in the fact that there is someone lower on the totem pole of understanding than himself. How did he come to know this? Has he spent thousands of hours researching the various accusations of conspiracy alongside their claims and available evidence? Is he aware of what the most common conspiracy theories claim specifically? I am afraid not. No, his belief in the impossibility of conspiracy emerged from the most telling and ironic source imaginable, an American intelligence agency.

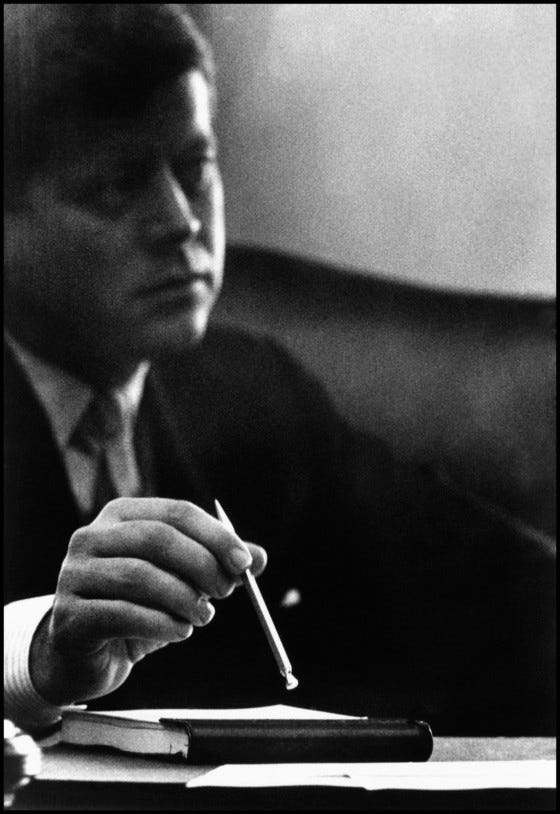

CIA memo 1035-960, “Concerning Criticism of the Warren Report,” was, as its name suggests, part of the agency’s counter offensive against the Warren Commission's critics. The commission claimed that Lee Harvey Oswald, acting alone, shot and killed President Kennedy as his motorcade drove through Dallas, Texas in 1963. The memo instructed CIA station chiefs, the heads of CIA offices around the world, to use their media assets to push the following claim: that nothing of any magnitude could be kept secret. At the highest levels of power, we were told, there are so many people involved and such high levels of scrutiny that everything is known. Conspiracy theories are thus necessarily false. Naturally, this ruled out a plot from within the US government to assassinate a sitting President. Skeptics of the Warren Report were given the unflattering label of “conspiracy theorist,” and in the end, the American people moved on despite a lack of compelling answers or serious investigation into the matter from the US government.

The “secrecy is impossible” defense of the Warren Report was a success. In fact, it worked so well that it became the blueprint for a communications strategy which would be deployed by all kinds of institutions in their efforts to curb the growth of alternative views. Rather than do the work of refuting these views one by one, institutions now rely on this single idea, one which is all the more comfortable due to its repetition, to sweep aside any and all dissent as a priori wrong. Unconventional positions now fall into the category of “conspiracy theory.” And as we all know, conspiracy theories are necessarily “kooky” and “ridiculous.”

Peace activists, climate change skeptics, critics of vaccination, historical revisionists, proponents of human biodiversity, opponents of unrestricted global trade or the global banking system, unrelated groups of all kinds would eventually be tarred with the conspiracy brush, which today has come to signify that one’s views are harmful, as opposed to merely ridiculous. The harm, we are told, is opinion based on misinformation. In the decentralized world of the internet, it is easy for misinformation to circulate, leading people into false realities and driving resistance to policies which are (allegedly) making the world a better place. The effect of this dynamic of accusation and antagonism, combined with institutional control of the dying but still powerful legacy media apparatus in an era dominated by the internet, has been to make conspiracy theories more pervasive and widespread than ever before. Yet at the same time, they have never been considered more taboo or more dangerous.

A few examples will illustrate this fact. No matter the average American's point of view regarding the events of January 6th, 2021, he will inevitably brush up against conspiracy. The establishment claims that President Donald Trump plotted with his supporters to seize control of the U.S. Capitol building as a way of overriding the democratic process. Others contend that elements within the American deep state used agent provocateurs embedded in the crowd to incite the appearance of a riot, tricking peaceful protestors into entering the Capitol, and then framing President Trump for the “crime.” Or consider another example, which was first pointed out to me by the Twitter account Unconscious Abyss. Multiple former members of the US intelligence community with high-level security clearances have now come forward to say that “they are convinced that objects of undetermined origin have crashed on earth with materials retrieved for study.” These objects are allegedly held by what the New York Times described as the “Pentagon’s UFO unit,” the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA). Reputable intelligence officers are, in other words, hinting that aliens exist and may have come into contact with Earth.

In today’s world, there is almost no way to take a position on anything of importance and avoid the implication that a conspiracy is afoot. Did President Trump attempt a coup? Conspiracy. Was he framed by the deep state? Conspiracy. Are members of DIA lying about the existence of aliens in some psychological operation? Conspiracy. Or are UFOs real? Again, conspiracy. Both sides of a huge range of important issues can justly be called conspiracy theory. And so the average person finds himself in a position of extreme cognitive dissonance. He defines himself in opposition to a category, conspiracy theory, which he cannot help but also be implicated in. This is no insignificant burden. The average American must constantly assuage the angst generated by their own ambivalence, and must do so skillfully. He cannot risk this inner division ever rising to the level of consciousness.

But because we live under a system with an at least nominally democratic process, his inner conflict is never far from the surface. The problem lies in how the near ubiquity of the conspiracy accusation has had the second-order effect of making such accusations arbitrary. Consider again, the issue of January 6th. The side that is considered “conspiracy” versus the side that is “reasonable” and “‘establishment” will be determined only by which has won the most recent election. Not only does the average American bear the weight associated with holding two incompatible beliefs, there is now deep anxiety associated with the risk that his political team might lose. The object of this anxiety is both material—what will happen to me in practical terms if my side loses power?—and also psychological—am I strong enough to handle becoming that which I have long disdained, a vulgar and ridiculous outsider, a conspiracy theorist? That such a large number of Americans, people who are trying to avoid “conspiracizing” if anything, still face this underlying dilemma, shows the entire framework around conspiracy theory has broken.

A closer look at the logic of the CIA’s claim regarding the impossibility of secrecy confirms the inevitability of this breakdown. Recall that this anti-conspiracy position asserts that among the powerful, those who run the government, large corporations, etc. secrecy is impossible due to the large scale of the operations involved. Not only are these organizations and their leaders intensely scrutinized and monitored, they involve thousands of potential whistleblowers, leakers and on. This idea feels true, because it is a tautology. If certain people or groups were able to hide their activities from the public, we would have no idea, precisely because those activities were secret. By definition, anything secret will be beyond our perception. The bald claim that everything is out in the open tells us nothing. Veteran CIA officer Ralph McGehee’s book, Deadly Deceits, shows the problem perfectly. McGehee’s work is half memoir, stories about his time in the agency, and half original research conducted after he retired. The reason so much additional research was required is because McGehee was mostly unaware of the agency’s broader goals and activities, even in countries he was stationed in.

Consider another example, the Manhattan Project. What is possibly the greatest scientific achievement of the twentieth century, the atomic bomb, was developed in absolute secrecy. Until the weapons were unleashed on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the public had no idea the program or technology existed, and in a way, neither did those inside the project itself. Secrecy was maintained through compartmentalization, a technique central to military intelligence and special operations tradecraft. Workers and scientists were told only what they needed to know, and communication was forbidden. No one could leak the entire project, because no one part understood the whole.

But there is a more fundamental problem, namely that the argument against conspiracy theories reverses the conspiracist’s position. A conspiracy theory necessarily refers to events which have not been hidden. Had they been, theorization would be impossible. Thus, the objection that all conspiracy theories must be false because they allege hidden dynamics makes no sense. Conspiracy theories make the opposite claim: the dynamics are not hidden and are available to be understood through whistleblowers, declassified documents, primary sources, and so on. Marshall McLuhan once quipped, "only puny secrets need protection. Big discoveries are protected by public incredulity." What often shields high-level criminal activity is not concealment, but the refusal to believe that anyone would act so brazenly.

Why did the public not just accept, but internalize and embrace, an argument which collapses at the slightest challenge? While the idea that secrecy is impossible may not be empirically correct, well formulated, or even logical, it is flattering. What it asserts, in essence, is that the public already knows everything, that the American people are too clever to be fooled, and the American system of government too well constructed by its founders to ever be abused. Comforting assertions, but false ones.

Despite this flattery, there is an even deeper subtext to the anti-conspiracy position that puts the average person in a compromising situation. The underlying claim is that the political class cannot successfully plot, cannot conspire, because insiders are aware of the high risk of exposure. Thus they would not even attempt such activities, knowing they would fail. We reach the inevitable conclusion, then, that the only people who would plot, conspire, or attempt to do large-scale wrongs, are those lacking formal power and its attendant scrutiny, i.e all of us. What appears to be self-evidently true, reassuring, and complementary turns out to be the opposite, a kind of conceptual judo which preemptively absolves the politically connected of any wrongdoing and reflects suspicion back on the average person.

The American public has taken on psychological baggage, the burden of constant suspicion, and given unlimited license to our political class, all in exchange for the illusion of self-esteem, of superiority, over kooks. And even this paltry benefit would fade away, as the eventual omnipresence of conspiracy theory—both as accusation and as narrative structure in politics—would force the public to become the very thing it sought not to be, conspiracists. A faustian bargain if there ever was one.

But our soul is not lost. Having seen that this state of affairs was founded not on reason, but propaganda, we can to return to ourselves, and rediscover the art of adjudicating matters of fact based on the evidence, rather than false categories contrived by managers of public opinion. We must let go of “conspiracy theory.”

Brilliant article and I myself haven't thought of the problem this deeply if at all...